Hello everybody! After J.J. Johnson’s death in 2001, Commander Trombone published the article below:

J.J. Johnson: Thank You Very Kindly

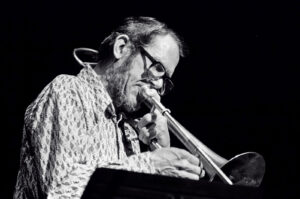

J.J. Johnson

n the

At the Opera House recording J.J. Johnson made with saxophonist Stan Getz, the crowd applauds enthusiastically after J.J. finishes one of his choruses. The trombonist can plainly be heard saying, “Thank you very kindly.” J.J. Johnson, the master jazz trombonist who always accepted appreciation with grace, died on February 4, 2001. His career has been recounted many times, but his remarkable personal qualities are less well known. Despite the fact that musicians and critics consistently heaped praise on him for his expertise with the trombone and his overall musicianship, he remained a humble man his entire life, quick to give others credit and slower to discuss his own accomplishments. But J.J. often revealed something about himself when he talked about peers, colleagues, or leaders he respected. In a 1994 interview conducted by David and Lida Baker, Johnson described Benny Carter, one of his earliest employers and role models, but he could have been describing himself:

He was a brilliant musician, he was a brilliant arranger, a brilliant composer, a nice person to know-he exuded professionalism in his demeanor-when he would talk to an agent or musician or to YOU about your part . . . at rehearsal. He exuded this air of professionalism and dignity and courteousness that was quite extraordinary. He was an extrordinary man, and still is.

The realities of a working musician were something J.J. was familiar with, and Johnson had what he called the “battle scars” gained throughout his career to prove it. His focus, however, remained music: getting it out the end of the trombone or into an arrangement or composition. J.J. will certainly — and understandably — be remembered for having transferred the complexities of be-bop to the trombone with stunning technique, but there was more to it than that. It was musical clarity that J.J. was after. And like Miles Davis (who was a good friend), Johnson understood that a small musical gesture, properly presented, could loom large. As much as anywhere, the connection between the two men’s improvising styles is evident on Walkin’, which J.J. recorded with Miles in 1954. Like Miles, Johnson’s musical world kept expanding, and J.J. believed the music known as jazz should keep expanding, too. In a 1990 interview conducted by Lida Baker for Instrumentalist magazine, J.J. explained it this way:

Jazz is by its very nature is a very restless music. It won’t stay still; it won’t behave. You can’t just put over there and say, “Now be quiet and don’t say anything.” It won’t allow that. It must evolve; it must reach out and explore. When Dizzy and Bird came on the scene there was a hue and cry, “What is this crazy music with flatted fifths called be-bop?” Obviously, it prevailed. I think it will always be like that. When something new comes along there will be resistence to it at first. When Miles Davis recorded Bitches Brew there was a great hue and cry from the critics, the media, from everybody but especially his adoring fans. They raised a big ruckus about it. “He can’t desert us and go off into another world like that,” they said; but that’s what he did.

Johnson’s own musical journey started, in part, with a life-long appreciation of saxophonist Lester Young’s improvising. “I became a Lester Young a-holic,” J.J. remembered. “So much so that I could hum any one of his solos on any one of his recordings verbatim, just from listening over and over and over to a particular cut on a given lp . . . ” From there, J.J.’s musical life kept growing-from innovative and impressive sideman to leader, from arranger of pop tunes to composer of televison and movie scores, from an appreciation of Lester Young, to an appreciation of Hindemith, Stravinsky and Ravel. J.J. wasn’t above listening to “Rock” music either, and purportedly at one time had a fair amount of “Country and Western” in his record collection-but the grounding in jazz remained. As Johnson once put it in a 1970 Downbeat article, “I am a jazzman — first, last, always. But I feel that I must draw on all music to consider myself a complete musician.”

Not a technophobe

J.J.’s musical forays were augmented by interest in many subjects, including electronics. At one point, he assembled hi-fi equipment from a Heath kit. During the period in which J.J. was employed by MBA in New York, he was dispatched to Trumansburg for training on the Moog synthesizer, making him one of the first to understand how the new instrument worked. Johnson became involved with computers and Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) later, and in his last years spent time composing MIDI compositions for his own amusement which he then archived with the help of a CD burner.

J.J. Johnson in the Internet Age

J.J. Johnson

In 1996, Matt Calvert, a trombonist in the Bay Area of San Francisco, decided to create a web page devoted to J.J. Johnson. Calvert was surprised when J.J. discovered the web site and made contact through e-mail. Soon the two were talking on the phone on a regular basis. Eventually Calvert added a discussion/mailing list to the website in 1998, and musicians from all over the world began to subscribe. The topics discussed on the list ran a gamut from J.J.’s recordings, jazz, other important trombonists, and music in general. When activity on the list was slow, J.J.’s posts proved to be the biggest catalyst in getting things fired up again. His posts, while often about music, could be about nearly anything and were often entertaining. There were occasional controversies on the J.J. mailing list-the real kind and the fake kind provoked by the occasional persistent e-mail exacerbator known on the internet as a “troll.” While heated discourse was never J.J.’s style, he often mentioned on the list that he found the disagreement interesting and provocative. “I’m no goody-two shoes,” Johnson once commented on the mailing list.

A Legacy of Great Recordings

J.J. made hundreds of recordings in his lifetime, some as a leader and some as a sideman. Understandably, he made so recording dates he couldn’t always remember the specific circumstances of each. “I hope the record will show I recorded with Charlie Parker,” J.J. Johnson said in an interview for the Global Music Network. He did, in 1947. He also recorded as a sideman with Sonny Stitt, Sonny Rollins, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Horace Silver, among others. His performances as a sideman are always excellent, but on recordings where J.J. is the leader he is able to bring to bear the full level of his ability as a improviser, composer and arranger. The groups involved might be as small as a quartet (First Place recorded for Columbia records), or as large as a big band (The Total J.J. Johnson originally recorded for RCA Victor. The Brass Orchestra recorded for Verve in 1997 is another good example.) Which recordings are the classics? Well, J.J. Inc is excellent. The Eminent J.J. Johnson Vols 1 and 2 are known for their quality. Proof Positive, recorded for Impulse! is a Tour de Force. In truth, though, which J.J. recording is the classic depends on who you ask. One thing is for certain: it is nearly impossible to imagine a bad J.J. Johnson performance. It’s no wonder that he won Downbeat polls for trombone year after year.

Missing in Ken Burn’s Jazz

Johnson was not mentioned at all in Ken Burn’s recent and controversial documentary Jazz. Certainly, J.J was in good company-many important jazz artists were not mentioned either. Yet it still is a shame that a career so full of artistry, mastery, craftmanship, growth and staying power could have gone unmentioned. Some of J.J.’s performances as a jazzman did find their way onto film, kinescope (a film recording of a television picture), and video footage. One of the very best-and most recent-was an amateur video shot in February of 1991 at Kentucky State University, now distributed by Jamey Abersold because Johnson’s performance was so outstanding. (The Global Music Network video link, above left, is another version of the same concert.)

In 1987, J.J. Johnson, not long back into the jazz scene after spending years in California composing for television and movies, played at the Village Vanguard with his newly formed group. The jazz critic Stanely Crouch described J.J. and his triumphal return for the Village Voice:

On opening night, the house was full of enough trombonists to create a brass shortage had the Vangaurd blown up. Slide Hampton presented Johnson with a scroll signed by many fellow trombonists who wished to express their love, respect, and best wishes for the master. It was fitting, and Johnson, who embodies the dash and grace at the center of the feeling of jazz, stood there radiating the aristocratic glow of those who have been chosen by nature to provide flesh and blood examples of poetic excellence. Though there have never been many, few of his kind will always be enough.

Certainly Crouch is right — few of J.J.’s kind will always be enough — but of course what this means is that it will always be more difficult to say goodbye.